New York Illustrated News – June 15, 1861

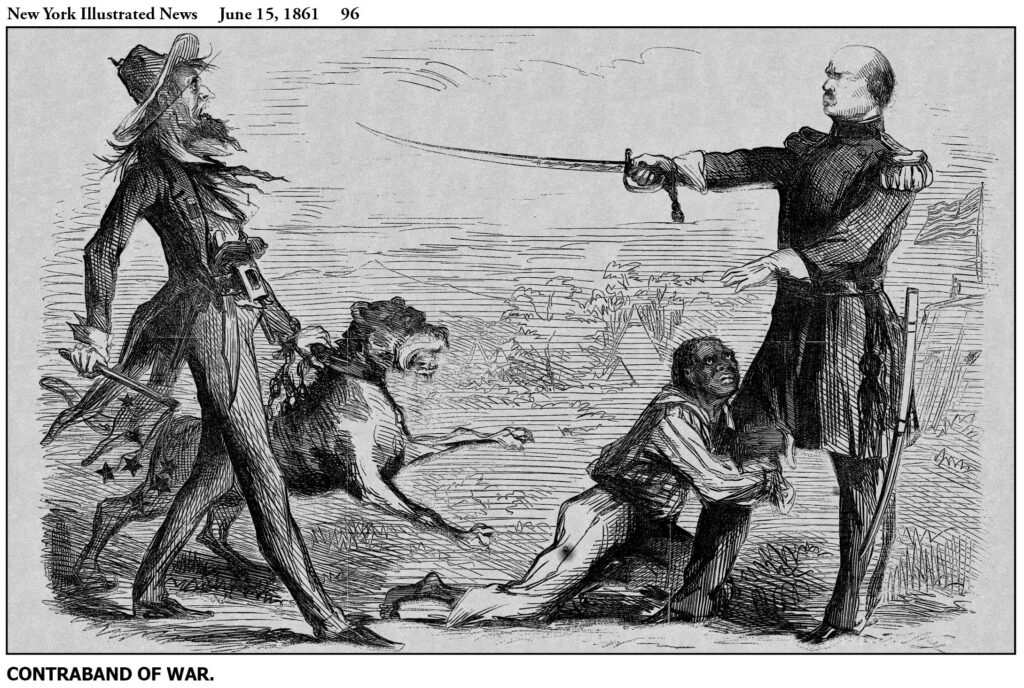

When the Civil War began in April 1861 with the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Nast was working for the New York Illustrated News. Two months later, he depicted Major General Benjamin Butler holding one of the artist’s first Southern stereotyped villains at bay.

On May 22, 1861, Major-General Benjamin Butler took command of Fortress Monroe. Butler would become a future target of more than 65 Nast cartoons, but at this point he was on the side of Union angels as the initiator of an extraordinary turning point in Northern public opinion about slavery.

The next day, three slaves arrived at Fortress Monroe in a stolen rowboat, fleeing across the James River from constructing artillery across the harbor aimed directly at Butler’s fort. They believed their owner was planning to send them to North Carolina to build more fortifications.

Butler was a skilled lawyer and politician from Massachusetts. He was familiar with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which Nast had learned about from his art teacher, Theodor Kaufmann. He understood that Lincoln had no intention of interfering with slavery at this early point in the war, but also knew that as a military commander, he had the right to seize any enemy property that was being used for military purposes.

When the owner’s military emissary showed up to reclaim his slaves, Butler refused on the grounds that Virginia had seceded, and now as a “foreign country,” it had no continuing rights under the Fugitive Slave Act. Since the South considered slaves as property, Butler would treat them as property too, and hold them as “contraband of war.” The early trickle became a flood. Within three weeks, there were 500 contrabands within Fortress Monroe. Nationally, the hundreds eventually became tens of thousands during the course of the war.

Lincoln and his Cabinet passively agreed not to overrule Butler and the term “contrabands” quickly gained common usage on both sides. Two months later, Congress actively supported Butler by passing the First Confiscation Act. The more subtle aspect of the term “contraband” was that Unionists could readily support the principle of confiscation, while the idea of emancipation was premature at that time, except to a minority of dedicated abolitionists.