Harper’s Weekly – January 24, 1863

Although the victory at Antietam was not decisive — as it could have been under a general like Ulysses Grant — it was still sufficient for Lincoln to proclaim that all slaves in states and/or territory within states controlled by the Confederacy would be emancipated on January 1, 1863.

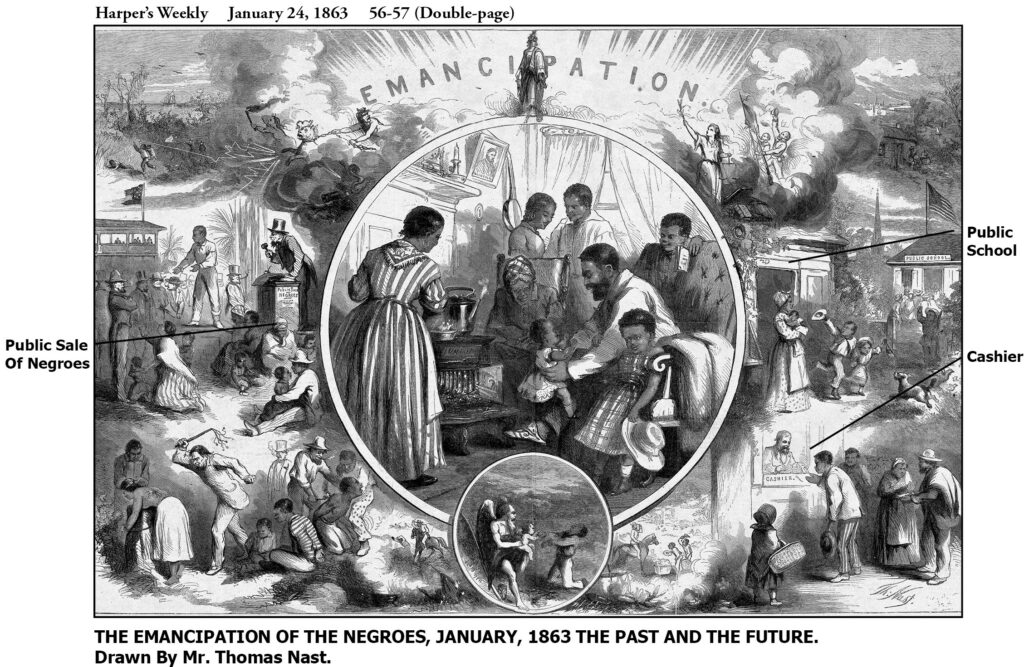

Nast put a great deal of effort into his portrayal of Emancipation. The preliminary sketch in his Civil War scrapbook suggests that he began work shortly after Lincoln’s September announcement. His strong double-page allegory was twice rejected by John Bonner, the Weekly’s pro-slavery editor. However, three months later when the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, Bonner was gone and George William Curtis began his thirty-year career as editor. Harper’s Weekly printed the complete text of the Proclamation.

The Emancipation of the Negroes finally emerged as a dramatic allegory in the next issue. The dominant center highlighted “a negro’s free and happy home” where “the reward of faithful labor . . . belongs to the laborer only;” it included a framed image of Lincoln and a banjo on the wall, with “Union” inscribed on the stove. Below, Father Time had Baby New Year in his lap, who struck the shackles from the ex-slave on his knees. The horrors of slave life — whipping, branding, auctioning, being shot, chased by dogs — were depicted in excruciating detail on the left, contrasted with the benefits of public schools and paid work opposite.

Nast reached new artistic heights with his symbolized visualization of what the Proclamation would mean. No other illustrator or caricaturist of his era used such dramatic realism, detailed facial expressions and so few explanatory words — Public Sale of Negroes, Cashier, Public School — to capture its essence. His sketches spoke for themselves.