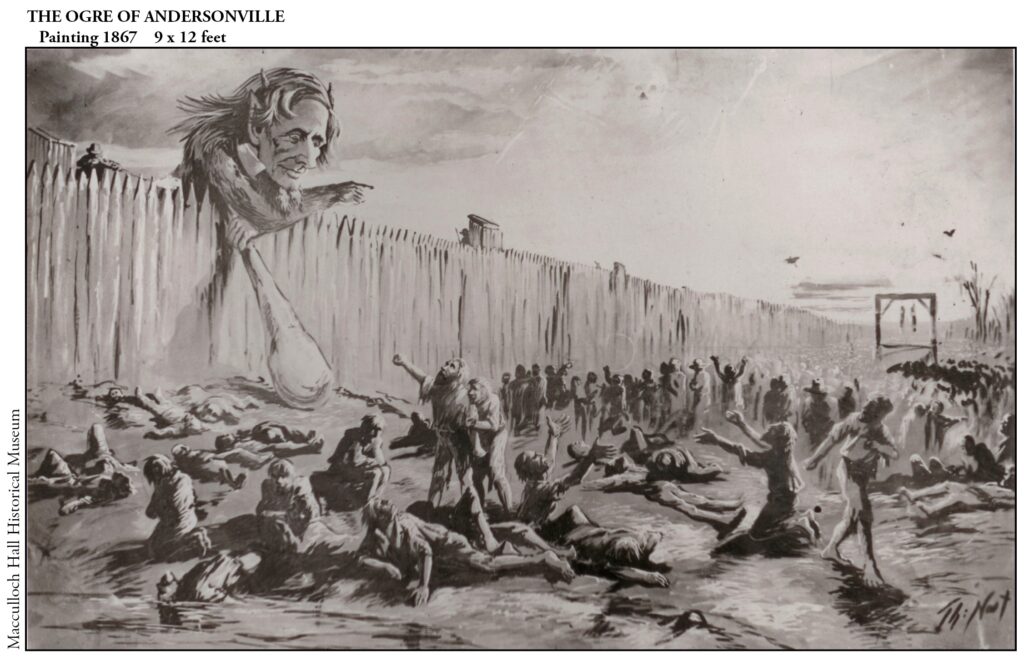

Painting – 1867

Nast never depicted Georgia’s Andersonville Prison during the course of the war. Unhappy at Harper’s Weekly because of conflicts with his editor, George William Curtis, Nast left for a year at the end of May 1867. He spent the next six months creating a moving panorama consisting of 33 nine-by-twelve foot panels dealing with slavery, the Civil War and sectionalism. Called the Grand Caricaturama, it played in New York and Boston, and was an artistic success but a financial flop.

The Ogre of Andersonville depicted Jefferson Davis with devil’s horns and a monstrous club while leaning over the stockade and pointing to two Union prisoners hanging from a gallows.

Davis was vilified most for the inhuman treatment of 45,000 Union enlisted men in Andersonville Prison from February 1864 until almost the war’s end. The men, who had been transferred from Belle Isle in Richmond, were deprived of most of their clothing and other possessions and given sparse rations of corn meal and beans. Malnutrition, poor sanitation, crowding, and exposure to Georgia’s hot sun and humidity in the summer and cold in the winter, led to chronic diarrhea, dehydration and death. Discipline was strict, and men were shot on sight for approaching a “death line.” 13,000 died.

Commandant Major Henry Wirz was tried and convicted in September 1865, when the shocking revelations of Anderson’s horrors were front page stories. Wirz was hanged on November 10, the only Confederate executed for his military actions by the federal government after the war was over.

As a reviled impersonal symbol of the Confederacy, Andersonville was unsurpassed. A major issue at that time was whether Davis knew what was happening at Andersonville and, if he did, whether he too should be executed. The first question was never answered and he was never tried, although for other reasons.

On May 10, 1866, a year to the day after his capture, Davis was indicted for treason. Davis agreed that treason should be punished if committed by a citizen of the United States. His defense was that he had given up his citizenship when Mississippi seceded, and therefore he owed no allegiance to the U.S. As time passed, his trial was postponed several times. Public opinion, including Harper’s Weekly, changed to oppose prosecution because there was nothing to gain; on the contrary, a ruling that the seceding states had the right to do so, could have upset the de facto applecart that victory had provided the Union with respect to secession.

Davis was confined at Fortress Monroe for two years under relatively easy conditions. His personal guards were removed after several months, and he was free to walk the grounds. On May 13, 1867, Horace Greeley and others signed a $100,000 bail bond, and Davis was a free man.