Harper’s Weekly – September 27, 1884

Blaine was proud of his Congressional achievements. He was elected to the House in 1863, served three terms as speaker (1869-1875), and became a Senator late in 1876. In 1881, he served briefly as James Garfield’s Secretary of State, where he was involved in another scandal involving a questionable guano and nitrate claim in Peru by an American citizen, Stephen Elkins, who would become his campaign manager in 1884.

After Garfield was assassinated, Blaine resigned from President Chester Arthur’s cabinet and took time off to write his memoirs: Twenty Years of Congress: 1861-1881 (Lincoln to Garfield). It was published in two volumes, the first in the spring of 1884 — timed to coincide with the start of his Presidential campaign — and the second in 1886. (Earning Blaine $200,000-300,000.)

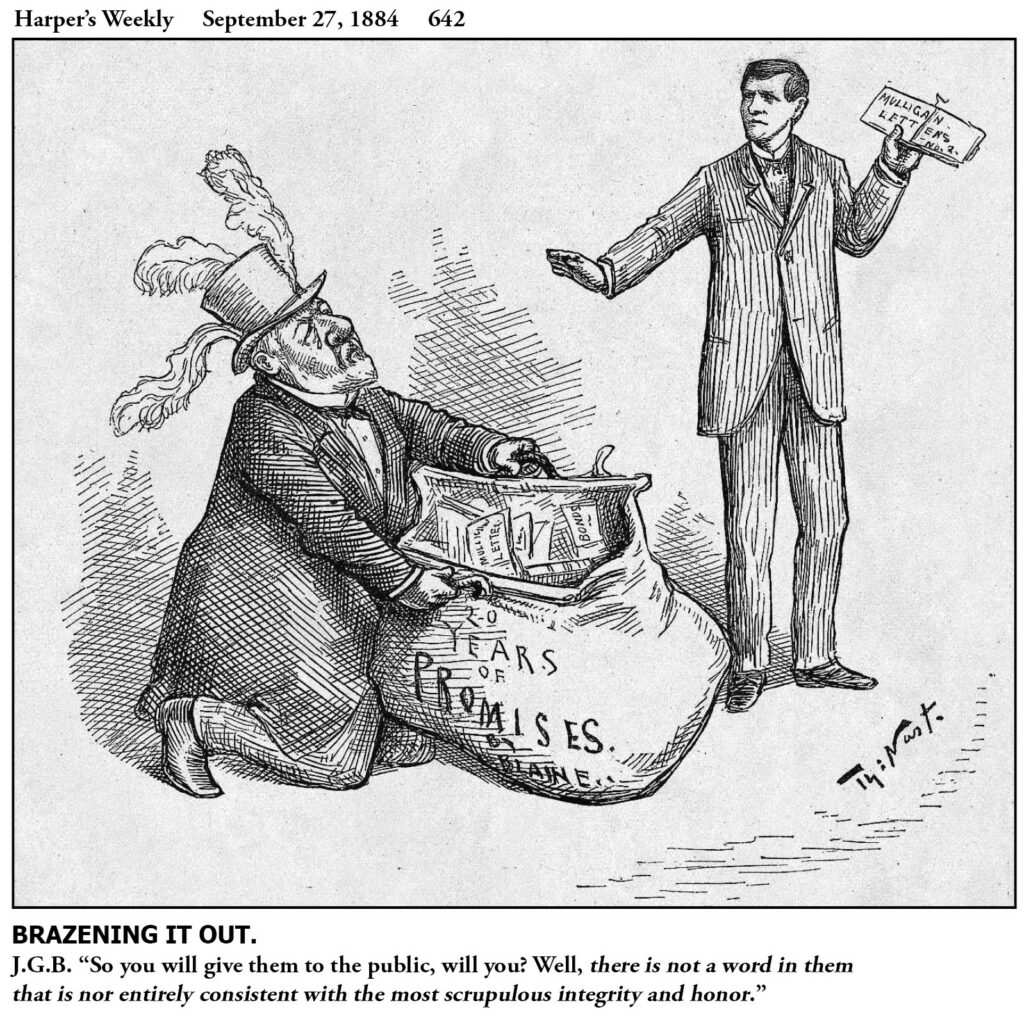

Nast used the title to taunt Blaine by tagging his carpetbag with “Twenty Years of ______,” just as he had labeled Horace Greeley with “What I Know About ______” twelve years before.

This was one of six Nast cartoons attacking Blaine in the same issue, after more incriminating so-called Mulligan Letters came to light. Blaine’s carpetbag was stuffed full of newly-revealed Blaine correspondence to Warren Fisher, as well as bonds of the Little Rock and Fort Smith railroad. (Fisher was a contractor for the railroad and a partner of Blaine’s brother-in-law). The scandal had first erupted in 1876 when James Mulligan, Fisher’s disgruntled former clerk, had brought the letters to the attention of the House Judiciary Committee investigating Blaine. He read favorable extracts from the letters, lied to the committee, and subsequently tricked Mulligan into letting him look at the letters, and then absconded with them.

On August 5, 1884, mugwump Carl Schurz gave a 49-page speech in Brooklyn, claiming that the Mulligan letters by themselves should disqualify Blaine. His scathing tirade was widely distributed in print.

A month later, Schurz was contacted by a Boston law firm which had additional Blaine-Fisher correspondence belonging to its client James Mulligan. After delegated Mugwumps met with Mulligan and inspected the letters, they were published on the front page of the The New York Times and in other papers on September 15, seven weeks before the election. Blaine acknowledged their authenticity, claimed they reflected his integrity, and encouraged Republican newspapers around the country to reprint them — consequently reviving the public’s interest.

However, one letter marked confidential blew up in Blaine’s face. It had been written eight days before he made his melodramatic defense on the floor of the House on April 16, 1876, reading parts of the original batch. It asked Warren Fisher to do him “a very great favor” by copying and immediately returning a draft of an enclosed letter from Fisher to Blaine distorting the facts and exonerating the candidate.

Blaine’s transmittal letter closed: The letter is strictly true, is honorable to you and to me, and will stop the mouths of slanderers at once. Regard this letter as strictly confidential . . . Kind regards to Mrs. Fisher. Sincerely,

(Burn this letter) J.G. Blaine

Fisher neither replied nor burned the two letters. They provided fuel to Nast and other cartoonists, as well as to marchers carrying torch-lit paper signs while chanting: “Burn this letter. Burn this letter. Kind regards to Mrs. Fisher.” The next issue of Harper’s Weekly included six Nast cartoons and Blaine’s game-changing letter.