Harper’s Weekly – April 16, 1870

A fundamental rift in America preceded the 1846 assumption of the Papacy by Pius IX. As the massive influx of Irish immigrants and potential voters increased annually, New York Governor William Seward wanted to attract them to the Whig (pre-Republican) party. During 1840-42, he pressed the State Legislature to fund parochial schools. He partially succeeded; the Maclay Law permitted funding but prohibited religious instruction in any school, thereby giving him and Catholics half their loaf as a first step.

The primary objective of Protestant education was to provide the same fundamental liberal education to both native-born and immigrant children. Protestants did not want their First Amendment rights inhibited, nor did they want tax revenues used to support parochial schools of any denomination.

Conversely, many Catholics rejected Protestant “common” schools because they objected to lessons in history and religion which denigrated the authority and practices of their Church. Especially aggravating were readings from the St. James (Protestant) Bible. Rather than have their children “corrupted,” they kept them out of school and then objected to their taxes being used to support those schools.

New York’s first Archbishop, “Dagger John” Hughes, was consecrated in 1850. He became the most powerful Catholic in New York, and an outspoken supporter of Papal supremacy (ultramontanism) two decades before Pius IX declared himself infallible. Conversely, he believed that the fundamental weakness in Protestantism was its failure to recognize and impose religious authority. A child immigrant himself, he empathized with Irish rebels in their efforts to free their country from Protestant England.

Dagger John was effective. He succeeded in getting funding for Catholic schools and real estate for Catholic orphanages, hospitals and churches, as well as schools. He allied with Democrats in Tammany Hall as Irish voters helped keep them in power. When the Civil War came, he supported the Union and helped calm the draft riots. At his death six months later, Harper’s praised him as wise and honorable, and noted the breadth of his social, moral and political influence. In retrospect, 21 years later when his “gentle and courteous” successor, John McCloskey (the first American Cardinal) died, the Weekly referred to Archbishop Hughes as “too active a politician and too polemical a prelate.”

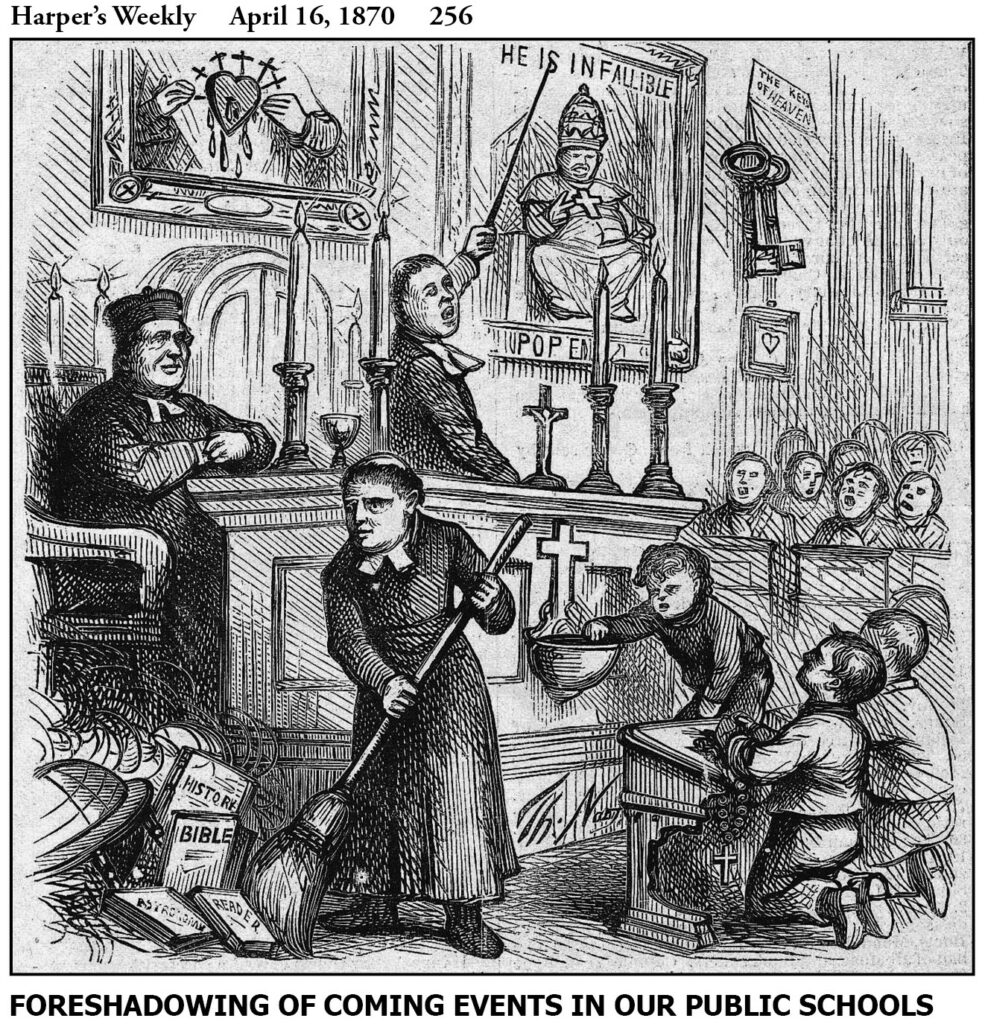

Those positive feelings about Catholic leadership in New York evaporated soon after Pius IX erupted. Taking their lead from the Pope, outspoken Irish-American priests and media advocated the abolishment of public schools. Nast counter-attacked, quoting three Catholic media and a bishop to that effect, while a priest swept away the Bible and current textbooks. Another pointed to the infallible Pope, close by the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven.