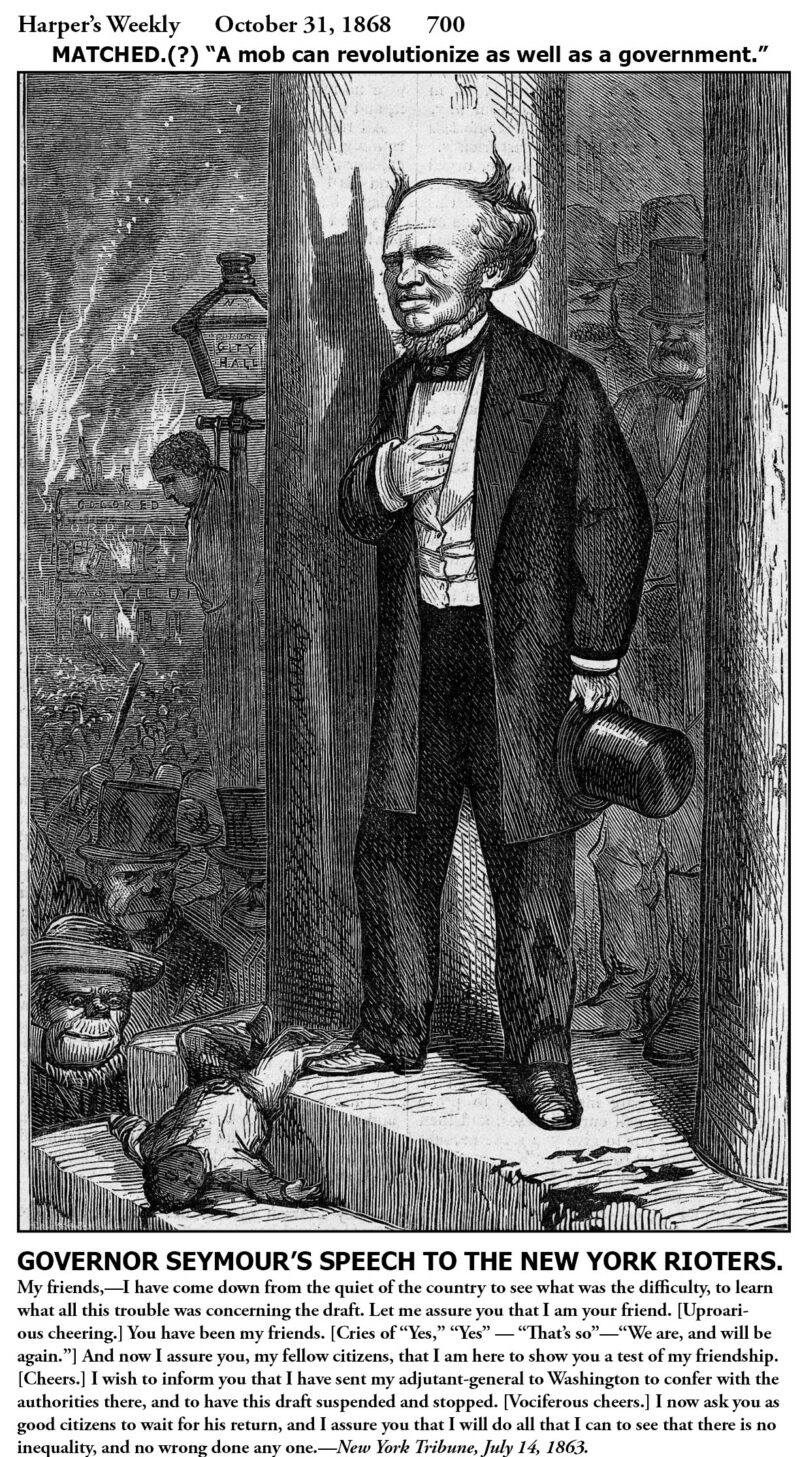

Harper’s Weekly – October 31, 1868

In 1868, Democrat Horatio Seymour ran for President against Nast’s idolized hero, General Ulysses S. Grant. The unshown left half of this cartoon featured a full-length illustration of Grant. Above him was “Let Us Have Peace,” his campaign slogan. Below was his July 3, 1863 demand to Confederate General John C. Pemberton for the unconditional surrender of Vicksburg. Nast contrasted this (“Matched?”) with Seymour’s belated speech to the New York City Draft Rioters eleven days later.

Nast used the imagery from those riots — which he had drawn at the time — of the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum and the lynching of a Black man hanging from a lamp post — as a symbol to stigmatize Seymour repeatedly during the campaign. He also twisted Seymour’s hair into devil’s horns.

* * * *

By early 1863, it became obvious to President Lincoln and Congress that the Union Army needed more men than volunteers could supply. Military reverses, sickness, desertions, and low morale were significant problems. Congress responded by passing the Enrollment Act, which authorized the president to draft men for a period of up to three years, and created the bureaucracy to do so. It also allowed draftees who could pay either a $300 commutation fee or, alternatively, provide a substitute, to escape the draft, thereby inflaming those who had no way out.

New York City was a tinderbox with its resentful and volatile Irish population also worried about freed Blacks coming North and taking their jobs as laborers. On Saturday July 11, the first draftees’ names were drawn at the provost-marshal’s headquarters. The names were published in the Sunday papers, and the pot began to boil. The next day, the worst riots that have ever occurred in this country exploded throughout the city and lasted four days. They were finally put down with the help of several regiments of soldiers who were ordered back from Gettysburg; it was their absence from the city that enabled the rioting to last as long as it did.

Monday’s arson, assault and murder was primarily the work of potential Irish conscripts and their friends and relatives, including many blood-thirsty women. By Wednesday, criminal elements took the lead in looting, lynching and other pillage. The police were attacked and killed, and no home or business that the mobs associated with Blacks or other anti-Irish social or political classes was safe. About 120 people died, including 21 Blacks, several of whom were lynched. Property damage was extensive.

Of all the horrendous atrocities committed by the mob during the riot, the most infamous was the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum in the late afternoon of Monday, the first day. The building usually was home to six to eight hundred children, all of whom were safely evacuated due to the quick thinking of the orphanage’s leadership. Located on Fifth Avenue between 43rd and 44th Street, just north of today’s New York Public Library, its property extended to Sixth Avenue. It was only two blocks from the 44th Street home that Nast and his wife Sallie had left ten weeks earlier.

Nast probably saw about 2,000 rioters attacking the Asylum. They ransacked the four-story building and its two three-story wings, even carrying away the children’s clothing, before setting it on fire. He sketched the horrific scene — no allegory . . . yet.

One horrific sketch that became a symbol depicted Hanging a Negro in Clarkson Street. The innocent cartman was beaten insensible, hung, and burned. Nast probably did not see this scene but recreated it from newspaper accounts.

Democratic Governor Seymour was the man to whom the stricken city looked to for leadership. He had been elected in 1862 on an anti-administration platform — as the Union army suffered continuing disappointments under General George McClellan — and was in tune with the Northern Copperheads who opposed the war, abolition and conscription.

In contrast to his fellow governors, Seymour deliberately avoided contact with the draft authorities. Unaware that conscription would commence the next day, he went on vacation to Long Branch, NJ, on Friday, July 10, and didn’t arrive in the embattled city until mid-day Tuesday. His first act proclaimed the city in a state of insurrection and ordered the rioters to desist.

Next, Seymour addressed the mob in City Hall Park, calling them “My Friends.” While his memorable salutation may have made sense under the circumstances, Nast repeatedly made sure that he would never live it down. In this cartoon, Nast also included an Irish ruffian looking at a dead Black child.