Harper’s Weekly – October 15, 1864

This is an extracted centerpiece from The Chicago Platform, Nast’s 20-vignette follow-up to Compromise with the South, and published a month before the 1864 election when George McClellan faced off against Lincoln.

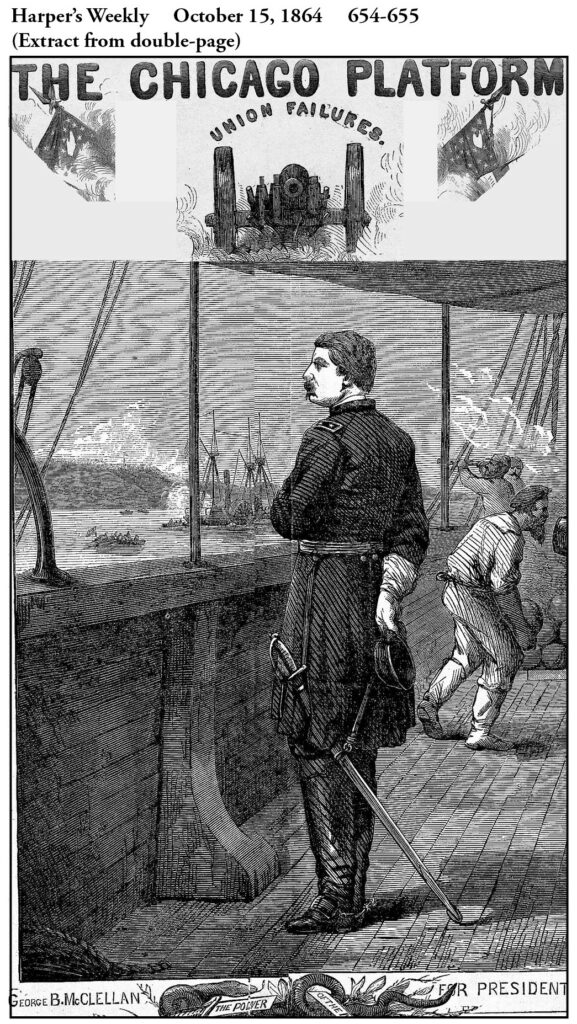

Nast’s prize slap in the cartoon was at McClellan standing on board a ship covering his backside with his cap. The reference was to the “Gunboat Candidate,” as McClellan was popularly mocked, going back to July 1, 1862, when as the Union General, he reportedly watched the Battle of Malvern Hill from the safety of the ironclad Galena in the middle of the James River, a mile away from the battle, in the finale to his failed Peninsular Campaign to capture Richmond. McClellan hesitated to use his numerically superior force because he erroneously believed that he was outnumbered by Lee’s army. Underneath the cowardly general was a copperhead snake breaking the sword of Northern power, just as Jeff Davis did in Compromise with the South. The cumulative focal point of Nast’s devastating attack on McClellan was to blend the general’s fearful battlefield style with his acceptance of a contradictory nomination that he must have found humiliating on occasion.

After General McClellan’s fifteen-week Peninsular Campaign ended disastrously at Malvern Hill, his failure to capture Richmond made it apparent to Lincoln that there would be no quick end to the Rebellion. Recognizing that all-out war would be required to win, Lincoln made a strategic military decision — not a moral one — to use his war powers to free all 3.5 million slaves under Confederate control. Doing so would add more than 100,000 men to the Union ranks, while enabling whites currently in support activities like cooks, teamsters or hospital workers, to become front-line soldiers; ex-slaves also would prove to be good infantry men. Equally important, the Confederacy which used slaves to support its armies in just about every way except the actual firing of its guns, would now find some of those roles more difficult to fill.

Lincoln presented his emancipation proposal to his approving Cabinet in July. However, Secretary of State William Seward wisely advised waiting until after a military victory so it didn’t look like a desperation measure, and the President concurred.