Harper’s Weekly – April 30 1864

While devastating to the country as a whole, the Civil War provided a tremendous boost to the newspaper business in general and to the illustrated press in particular. Radio was a half century away and photography was limited to still pictures. (Photographers needed wagons, chemicals, special apparatus, long exposure times without movement, and far more mobility to shadow moving troops than their equipment allowed.) Accordingly, the demand for artists who could and would follow the armies continuously to sketch the skirmishes and battles, and to fill in the lulls in activity with scenes of everyday life, was almost insatiable.

The “specials” as they were called put up with horrifying living conditions and ever-present danger of injury, sickness, capture and, not infrequently, death. Most of them were young and adventurous, and willing to accept hardship and danger. With the two notable exceptions of Alfred Waud and Theodore Davis, none of the Harper’s artists were at the front for all four years of the war, as burn-out and less hazardous or better-paying opportunities thinned their ranks. Nast and Winslow Homer worked from home in New York.

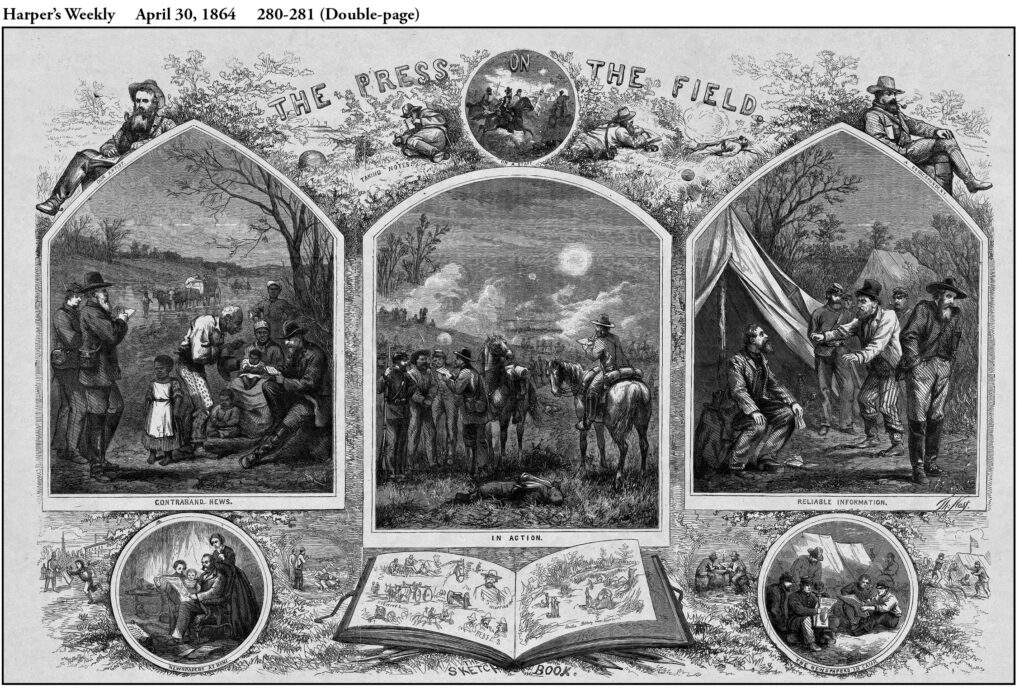

The War was three years old when Nast drew The Press on the Field. “Our artist,” shown at the upper left, was Thomas Butler Gunn, a close friend of Tommy and Sallie Nast. Nast’s small vignettes detailed an artist’s various activities: taking notes; sketching (a dead soldier close-up); getting the names of the wounded and dead (lower left center); drawing the complete picture from notes and quick sketches; and finally showing an original sketchbook. As Harper’s pointed out in its accompanying text, “that vast body of incident and adventure which finds no mention in official reports . . . is absolutely necessary to a proper appreciation of central facts and events.”