On July 30, 1866, Louisiana’s Republican Governor, James Wells, who endorsed Black suffrage, assembled a convention in New Orleans to draw up a new State Constitution. Recently-pardoned Mayor John Monroe and State Attorney General Andrew Herron mobilized the mostly ex-Confederate police to prevent the convention from taking place. They attacked the 25 delegates and 200 Black supporters, killing 34 Blacks and three white delegates, and injuring more than 100 others.

President Andrew Johnson had telegraphed Mayor Monroe in advance, telling him that any federal troops on hand — there were none due to a timing misunderstanding — would be expected to support the local authorities. The Massacre of the Innocents became notorious in the North with Johnson receiving well-deserved blame; he expressed no remorse or sympathy for the victims.

Nast had his dramatic response ready by October 1866 (as shown in his sketchbook at the Morgan Library in New York), but withheld it from publication for five months — until Johnson’s potential impeachment was beginning to simmer in the wake of a Congressional inquiry on the riot.

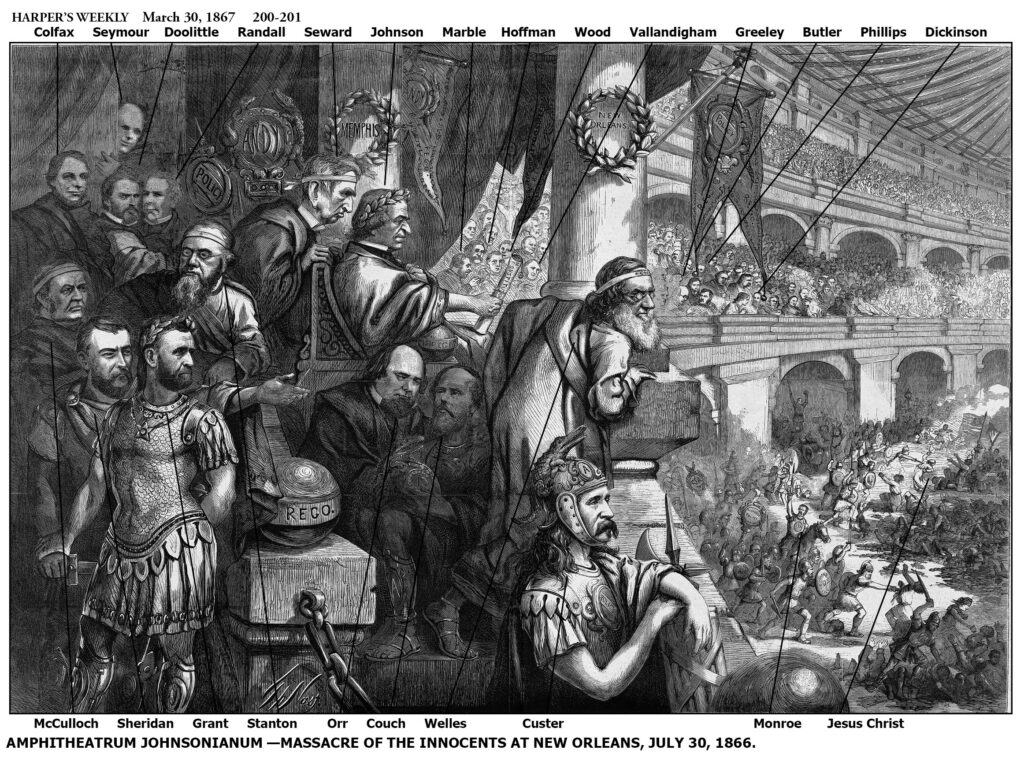

Eight months after the tragic event, Nast’s imaginative depiction of the New Orleans massacre used the Roman Colosseum as his setting. He portrayed Johnson as Nero, figuratively fiddling with the Constitution as New Orleans rioted, an illusion to his indifference to the massacre. Looking over his shoulder was Secretary of State William Seward as chief consul. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton turned his head away; Johnson wanted to remove him from office, while Stanton was determined to stay on and keep the President from interfering with the military in the South. (Eighteen months later, Johnson acted and impeachment followed.)

Monroe was leading his ex-Confederate police as they slaughtered the unarmed blacks on the Colosseum floor. Looking on were Cabinet members Gideon Welles (Navy), Hugh McCulloch (Treasury) and Alexander Randall (Postmaster General); Senator James Doolittle; Horatio Seymour who would run for Johnson’s job in 1868; and Copperheads Manton Marble, John Hoffman, Fernando Wood and Clement Vallandigham — Johnson supporters all. In the gallery on the other side, Johnson’s enemies — Horace Greeley, Benjamin Butler, Wendell Phillips and popular lecturer Anna Elizabeth Dickinson could be readily identified. Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, a Radical, monitored the scene next to Doolittle.

To highlight his Nero analogy, Nast pulled out all the stops and depicted a Roman gladiator in the act of stabbing Jesus Christ. He pictured them in white to make sure they stood out.

Directly below Johnson, diminutive Union General Darius Crouch was sitting in the lap of the much larger South Carolina Governor James Orr alongside a labeled Copperhead snake. The two had the featured roles at the pro-Johnson National Union political convention in Philadelphia two weeks after the riot.

Most important, Grant had a firm hand on General Phil Sheridan’s wrist, thereby inhibiting his unsheathed sword. (Sheridan was in charge of the Military District that included Louisiana, but had been away in Texas on the day of the riot.) Conversely, General George Armstrong Custer, a Johnson loyalist, watched the slaughter dispassionately.